The following has been transcribed, in its entirety, from an article of the same name in Chö Yang: The Voice of Tibetan Religion & Culture, vol. #6, with some slight editing for clarification of the English by a native speaker and the addition of a few pictures. It is reproduced here not out of wishing to claim this wonderfully precise, simple, and beautiful work as my own, but to share it for the benefit of all beings. I was fortunate enough to stumble upon the copy which is now in my possession upon a visit to the Norbulingka Institute in Dharamshala, and as far as I am aware, this magazine is only available in India to the Tibetans in exile. No longer!

The Buddha achieved enlightenment and taught his disciples his doctrine 2,500 years ago. Since we do not have the good fortune to have heard these teachings directly from him, we depend on the unbroken lineage of teachers and disciples as the basis for becoming a Buddhist. The purpose is to achieve liberation from rebirth in cyclic existence (Samsāra), and attain ultimate enlightenment for the benefit of all sentient beings. The Buddha is an object of refuge because, although he was an ordinary person to begin with, he was able to abandon all faults and achieve ultimate realization for the benefit of all sentient beings. The Dharma is the truth of the cessation of all disturbing emotions and their traces, and the truth of the path, which is the antidote to these disturbing emotions. This Dharma abides in the [mental] continuums of those who have realized the ultimate nature of phenomena. Because we depend on the Dharma to attain liberation, it is the ultimate refuge. The Sangha is like a reliable friend who has already attained liberation from cyclic existence and on whom the practitioner can depend for support in his or her quest for enlightenment.

Receiving initiation from a qualified master is a permission to recite the text(s), to meditate on the deity, and to recite the deity’s mantra. Without an initiation the practice of tantra is not only not permitted, but is also considered a cause for accumulation of grave negative karma for both the teacher and the disciple. Receiving the proper initiation gives the practitioner power to practice successfully and gain accomplishments. As stated in the following verse:

Without initiation there is no spiritual attainment,

Like a butterlamp of water.

Once the disciple has received initiation, the lama can teach him or her tantric practices and meditations.

Having received initiation into the three lower tantras, the disciple must practice the yoga with signs, which means visualizing the deity and reciting the mantra(s), which are practices for developing a calmly abiding mind. Once calm-abiding has been attained, the disciple practices the yoga without signs, which is meditation on emptiness, with meditation on the deity to develop special insight. Having received the higher tantric initiations, the disciple is ready to practice the generation and completion stages.

Yama distinguishes beings according to their accumulation of virtuous or unwholesome actions. In this way, he is the protector of virtuous beings, who are sent for rebirth in the higher realms.

Vaishrāvana is the protector of beings of middling capacity; those whose wish is to be freed from rebirth in cyclic existence and who adhere to ethics in the form of vows of individual liberation.

Vaishrāvana is the protector of beings of middling capacity; those whose wish is to be freed from rebirth in cyclic existence and who adhere to ethics in the form of vows of individual liberation.

Composed by Sangyé Nyenpa

This supplication was composed by H.E. Sangye Nyenpa Rinpoche in the early hours of 30th March 2012, in the presence of the precious remains of Kyabje Tenga Rinpoche. Immediatedly translated by Sherab Drimé (Thomas Roth).

Please note that words in parentheses are either the Tibetan/Sanskrit words for the term mentioned immediately preceding them---i.e. cyclic existence ("Samsara")----or the Wylie transcription of the Tibetan words, broken up into the appropriate syllables---e.g. lama (bla ma). All superscript numbers indicate my own notes, found at the end of the article.

This is dedicated in memory of Kyabjé Tenga Rinpoché. As of this morning, due to his supreme kindness and compassion the oral transmission of the Prajñaparamita Sutras is currently going ahead in Kathmandu without delay. Tenga Rinpoché considered them to be so precious and beneficial that nothing at all should get in their way, not even his own passing away.

Enjoy...

This is dedicated in memory of Kyabjé Tenga Rinpoché. As of this morning, due to his supreme kindness and compassion the oral transmission of the Prajñaparamita Sutras is currently going ahead in Kathmandu without delay. Tenga Rinpoché considered them to be so precious and beneficial that nothing at all should get in their way, not even his own passing away.

Enjoy...

Lama

The Buddha achieved enlightenment and taught his disciples his doctrine 2,500 years ago. Since we do not have the good fortune to have heard these teachings directly from him, we depend on the unbroken lineage of teachers and disciples as the basis for becoming a Buddhist. The purpose is to achieve liberation from rebirth in cyclic existence (Samsāra), and attain ultimate enlightenment for the benefit of all sentient beings. The Buddha is an object of refuge because, although he was an ordinary person to begin with, he was able to abandon all faults and achieve ultimate realization for the benefit of all sentient beings. The Dharma is the truth of the cessation of all disturbing emotions and their traces, and the truth of the path, which is the antidote to these disturbing emotions. This Dharma abides in the [mental] continuums of those who have realized the ultimate nature of phenomena. Because we depend on the Dharma to attain liberation, it is the ultimate refuge. The Sangha is like a reliable friend who has already attained liberation from cyclic existence and on whom the practitioner can depend for support in his or her quest for enlightenment.

The lama (bla ma), guru or spiritual mentor, is first mentioned in the refuge recitation because he relates the teachings—passed down in an unbroken lineage from the time of the Buddha—to his disciples. Therefore, if you really practice, the lama should be regarded no differently than the Buddha. Reverence for the lama is based on these reasons and through both the direct lama—that is, the one who bestows the teachings—and the indirect lamas—those in the lineage between the Buddha and the direct lama—are objects of respect. Special attention is paid towards the direct lama.

A master-disciple relationship is established when a disciple requests teachings and the lama or master agrees to give them. The master then transmits the teachings—which he has realized in his continuum—to his disciple. The wheel of Dharma has been turned when the disciple practices according to his master’s instructions and the master’s realization takes root in his or her continuum. In Tibet, such a master is called a lama.

There are many ways of categorizing lamas according to both the systems of sutra and tantra. In Tibetan Buddhism, tantra is considered the ultimate practice, but since all paths are studied and practiced simultaneously, it would be difficult to distinguish an exclusively sutra lama. One area in which a clear differentiation can be stated is in the giving of different types of vows. In this case, exclusively sutric designations are employed. These are lamas who give instruction.

There are eight types of vow of individual liberation. Five are for ordained people, and the lama giving them is called an ordained abbot (“Khenpo”). He explains the commitments contained in the vows to those who have decided to abandon the ways of lay[persons] and to adopt those of ordained persons. In the case of the vows of full ordination, [the lama] is called the full ordination abbot. The vows are preliminary female vows, male and female novice vows, and the male and female fully ordained vows. There are three types of vows for lay people. These are one day vows ("sojong"), and male and female lay vows. The lama who instructs disciples in lay vows is called a master.

Besides masters of the eight types of vows, there are other functions which lend particular names to the masters performing them. At the time of taking full ordination vows, there is a master who states the time and place of the ordination, a master of ceremony; a master for matters of discretion who takes the disciples aside and asks if there is anything about him or her that would make it unsuitable for the disciple to become a monastic; the master who gives reading instruction; and the resident master, one who is always there to be consulted concerning the vows as to what is permitted and what is not.

Within the sutra system, there are also lamas who pass on transmissions and who give explanatory teachings. A transmission (“lung”) takes place when a lama recites the a text passed down through a lineage of lamas to suitable disciples. Oral transmissions comprise reading important Buddhist teachings and are essential in that they ensure the integrity of the text and the continuation of the Buddhist lineage through generations of Buddhist scholars. If the texts were not passed down word for word and explanation or superimposed interpretation were added, the accuracy of the contents might change completely within the lineage of a hundred or so teachers with varying degrees of skill in oral expression. It is important in a religious person’s education that an explanation of a text accompany a transmission, and thus commentaries on texts are widely available, but the root or original text is kept separate and this is what is passed down orally in transmission.

Early signs of the potential danger of inexact transmissions were recorded in the years following the Buddha’s passing away [into parinirvāna]. During the Buddha’s lifetime, the teachings of the three categories of knowledge [Tripitāka] were retained orally in the minds of his various disciples. Because they were not written down, perfect memorization was essential. After some years, a council was held during which all the different teachings of the Buddha had given in different places were categorized. Later, when doubt arose as to changes in content due to mistaken recitation, other councils were held during which direct and indirect disciples cross-checked their knowledge to avoid inaccuracies. This tradition of transmission based on oral recitation is thought to come from this need to keep the teachings intact.

Explanation ("tri") is introducing the meaning of a text through interpretation and clarification. The teacher may either give an oral commentary based on his experience or knowledge of the meaning of the text, or base the explanation on commentaries written by his predecessors. The purpose of the explanation is to ensure that the text does not simply remain as an oral recitation, but that, through explanation, it may enter the disciple’s mind and cause his or her mental development.

From the tantric point of view, there are lamas who give empowerments, who transmit the lineage, and who give quintessential [pith] instructions.

Empowerment

Empowerment is very important, for in order to practice tantra, one must first receive initiation. In the lower categories of tantra, there is only the vase initiation. In the two higher categories of tantra, there are four initiations: the vase, secret, wisdom, and word initiation (or oral empowerment).

From the moment a practitioner has taken the vase initiation, the master bestowing it becomes his or her lama. Within the vase initiation there are several initiations, each related to the five Buddha families: Akshobya, the water initiation; Ratnasambhava, the crown initiation; Amitabha, the vajra initiation; Amoghasiddhi, the bell initiation; and Vairochana, the name initiation. In addition, there is also the master initiation. The lama bestowing the initiation is called the vajra-master.

Receiving initiation from a qualified master is a permission to recite the text(s), to meditate on the deity, and to recite the deity’s mantra. Without an initiation the practice of tantra is not only not permitted, but is also considered a cause for accumulation of grave negative karma for both the teacher and the disciple. Receiving the proper initiation gives the practitioner power to practice successfully and gain accomplishments. As stated in the following verse:

Without initiation there is no spiritual attainment,

Like a butterlamp of water.

Once the disciple has received initiation, the lama can teach him or her tantric practices and meditations.

Having received initiation into the three lower tantras, the disciple must practice the yoga with signs, which means visualizing the deity and reciting the mantra(s), which are practices for developing a calmly abiding mind. Once calm-abiding has been attained, the disciple practices the yoga without signs, which is meditation on emptiness, with meditation on the deity to develop special insight. Having received the higher tantric initiations, the disciple is ready to practice the generation and completion stages.

Transmission

All tantric teachings have their source in the sets of discourses. They are considered the fourth scriptural division, in addition to the three scriptural divisions of the Sutras: discipline (Vinaya), sets of the Buddha’s discourses (Sutras), and knowledge commentaries (Abhidharma). Tantra means continuum [or web]. Transmitting the continuum means passing on the tantric teachings, which have their bases in the original tantric texts. These texts include descriptions of unique tantric practices, methods of practicing tantra, and explanations of attainments reached when the practices are completed.

Quintessential Instructions

When giving quintessential [or heart-essence] instruction, the lama explains the profound meaning of a text in a way that is easily comprehended by disciples. There are aspects of tantric texts which are difficult to understand when merely read, and which [therefore] require a lama’s interpretation. The lama must either have experience of the matter at hand, which is best, or at least a profound understanding of what it means.

Experiential Teachings

The disciple meditates and—when he or she has achieved some experience—relates it to the lama who offers further guidance. The disciple adds this advice to his or her meditation, continues to practice and—on achieving new experience—relates that before receiving further instructions.

The Master-Disciple Relationship

In Tibetan Buddhism, where tantra forms part of most daily practices, the master-disciple relationship is considered the basis for all realizations. The lama, because of his or her essential role in translating the Buddha’s doctrine to disciples, is considered no different from the Buddha. The core of many practices is meditation on the merit field, in which the practitioner meditates on the root lama surrounded by meditational deities (“yidams”), Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, Arhats, Heroes (“Pawos”), Sky-dancers (“Khandros”), and protectors (“Dharmapalas”), and prays to them as a source of inspiration and merit for attaining enlightenment. The term “merit field” means a field where meritis planted; where it grows and flourishes in the disciple’s mind-stream. The deities in the merit field are all aspects of the lama. At the end of the practice, the practitioner dissolves them back into the lama, knowing that they are his manifestations. In order for this practice to be successful, faith in the lama must be unshakeable, for the disciple cannot proceed confidently on the path when burdened with doubts concerning the main object of guidance and inspiration. It is not a question of how important or how knowledgeable the lama is, but the fact that he or she is the personal link with all the beings in the merit field that makes him essential.

When a disciple who has once considered the lama as the same in essence as the deities in the merit field rejects the lama, it is very difficult to expect progress on the path. Meditation and devotion to the deities in the merit field cannot continue without the lama as they were all his or her emanations and blessings. A disciple who has rejected his or her lama cannot expect to continue receiving blessings and inspiration from the lama’s emanations, since they are one and the same. It would be like wishing to enjoy the shade of a tree after it has been cut down. Since the lama is the link to the Buddha trough the lineage, rejection of the lama greatly weakens of severs the link.

Personal Connections

One may have an affinity with a particular lama due to some connection from a former life. Two lamas may differ greatly in scholarship or reputation, regardless of which one or the other may arouse a special feeling [in the disciple] and give rise to great faith and joy. A single explanation from such a lama may have the power to arouse profound understanding in the mind. The same words uttered by th lama with whom one has no such connection may not have the same effect, and in spite of his or her great knowledge and fame, will not arouse faith in the disciple. In this way, karmic connections with particular lamas are considered very precious and powerful. If a lama teaches a disciple on the basis of such a connection, there is no limit to the great realizations which can be achieved, and to the speed with which they are achieved. If there is no such karmic connection, then realization is hard to come by.

For example, long ago in India, the followers of the yogi Tilopa achieved varying levels of realization by practicing his teachings. Though Tilopa was their lama and they were all equally his disciples, it was Naropa who achieved high realization due to his former connections, while others achieved less and some very little. Naropa’s disciple Marpa was highly realized and had heard teachings from many great Indian gurus. He had many disciples in Tibet, but it was Milarepa who was unique among them in that he attained ultimate realization in that very lifetime. Different disciples have different levels of merit, predispositions, and necessary attributes for attaining realizations which are particular to them. The power of their wishes for enlightenment, respect for their teacher(s), their effort and their wisdom also play an essential part.

Though they are highly important, the quality and method of the lama’s teachings are not the essential factor in the disciple’s realization. Rather it is the way, based on karmic predispositions, that the teachings can affect the particular disciple’s [mental] continuum and have the power to stop defiled thoughts and actions, inducing pure realizations.

In petitions, supplications and prayers to the lama, the disciples request blessings. This is an important practice as the power of the lama’s blessing on the disciple’s continuum does not depend on the lama, but on the disciple. If his or her faith and respect of the lama are very strong, the disciple will be receptive to the lama’s blessing(s). If feelings towards the lama are clouded with doubt and uncertainty, the lama’s positive influence on the disciple will remain limited, however realized the lama might be.

When the sun shines over a snowy mountain, the snow melts and water flows into the valley below. If clouds obscure the sun, the snow will not melt and the rivers dry up. Similarly, the disciple with faith in his or her lama(s) will be receptive to blessings, and their spiritual advancement will be affected, while the disciple in doubt will not reap such benefit.

Because progress in spiritual practice depends so much on the lama, the disciple must carefully consider a potential teacher before engaging in a master-disciple relationship. The disciple may try to observe if the teacher acts according to the teachings he or she propounds, whether the lama is compassionate, preoccupied more with spiritual or worldly concerns, of stable character and does not give rise to doubt, knows more than the disciple, and belongs to an unbroken lineage. Ideally a teacher should never tire of teaching a worthy disciple and accomplishing the welfare of others.

Since it can be difficult to judge for oneself the extent of a teacher’s knowledge, a prospective disciple can seek the opinions of others. However, once the relationship with the lama is established, it must be protected at all costs.

This may be difficult, for the lama is also a human being and a disciple will inevitably find faults in his or her character. In cases where the disciple did not observe the lama enough beforehand and begins to perceive faults too outrageous to cope with, still he or she should avoid outright rejection, criticism and/or confrontation, and remain as neutral as possible. In the case of ordinary foibles, the disciple should reflect on the faults of his or her own character, focusing on the lama’s positive aspects and the spiritual benefit to be gained from the relationship. The disciple should make up his or her mind that the lama’s positive aspects greatly outweigh whatever minor faults the lama might have. In the ordinary way, if you regard someone with great respect and affection, their positive side greatly outweighs the negative. It is all a question of perspective.

The Advantages of Relying on the Lama

· The disciple will come closer to Buddhahood. All sentient beings have the potential to attain Buddhahood. The lama teaches methods for attaining Buddhahood. Therefore, the teacher-student relationship enhances the potential for achieving the ultimate fruit.

· It pleases the Victorious Ones. The Buddhas only have wishes to benefit sentient beings. Therefore, anyone practicing the path of virtue and improving their own prospects of enlightenment will be a cause of rejoicing for the Buddhas. On the other hand, if the disciple does not rely properly on the lama, he or she will not please the Buddhas, no matter how many offerings made to them.

· The disciple will not be disturbed by interferences or bad company, nor be overcome by the power of disturbing/afflictive emotions.

· The disciple’s realization of the stages of the path will increase.

· The disciple will not be separated from the lama in future lives, nor fall into the lower realms of rebirth.

· The disciple will effortlessly achieve all his or her long and short term wishes.

Relying on a spiritual teacher causes a student to accumulate great merit. This merit renders his or her actions performed either for self or others highly successful. If you study and lead a life of virtue, merit will be accumulated which will lead to a better life and good rebirth, but it will not necessarily free you from cyclic existence (Samsāra). However, if the practitioner dedicates merit towards the attainment of enlightenment, it will become the basis for acquiring the wisdom that realizes the selflessness of persons and phenomena (i.e., all dharmas). Such realization is necessary whether you aspire to attain freedom from rebirth in Samsāra or the ultimate goal of perfect enlightenment for the sake of all sentient beings. Teachings on emptiness (“shunyāta”) will not appeal to persons with little merit, for their sense of self-existence will be too strong. When practitioners develop even intellectual appreciation of emptiness and can accept it in theory, the grip of cyclic existence is greatly weakened. Their view of reality is like a woolen garment which has been eaten away by insects on the inside, while retaining its shape externally.

If you do not have a lama, your knowledge and progress on the path will not increase. If you have a lama, but reject and despise him or her as described above, great negative karma will be accumulated and no merit or progress will be derived from your practice.

Yidam

The yidam (yi dam) is a meditational deity. It is an aspect of the Buddha, and of the lama. Tantra is the quick path which allows the ripe disciple to attain enlightenment in one lifetime. Empowerment is a means to ripen the disciple’s mental continuum and is a preliminary for tantric practice. During an empowerment, the Buddha—personified as the lama—takes the form of a meditational deity, places the disciples in the deity’s mandala [i.e. sacred circle or heavenly palace], and confers initiation upon them. The meditation deity is thus and indirect personification of the Buddha adopted in order to confer the initiation on the student.

During the empowerment, the lama or vajra master generates him or herself as the deity with clear vision and divine pride. The master instructs the disciples what to visualize and mentally places them in a mandala, or deity’s abode, symbolized by a sacred painting (“thangka”) or a diagram painstakingly made of sand. The lama then visualizes the deity before him or herself, and prays for the disciples to receive accomplishments, bestowing the empowerment upon them.

Having received the initiation, the student is allowed to practice tantra on the basis of the deity or yidam whose initiation he or she has received. When practicing the self-generation of the deity, the disciple first meditates on emptiness, out of which the deity arises. Therefore, in order to practice tantra successfully one must have at least a firm conviction that all phenomena are empty of inherent existence. Visualization of the yidam must be very clear, therefore meditative stabilization is necessary. Clarity of visualization is the antidote to ordinary appearances [and perception].1 The strong identification with the deity, known as “divine pride,” is the antidote to grasping onto ordinary appearances.

Yidams are Buddhas by nature. They are beyond the cycle of rebirth [i.e. birth, aging, sickness, and death, ad infinitum] and, in the context of the merit field, they are placed on the four highest levels of the [refuge] tree. Lama and yidam, mentor and deity, should be revered equally and seen as indivisible from one another. Anyone who claims that yidams are superior to lamas will not attain realization. Those who consider them equal will gain high spiritual attainments.

When Marpa went to India for the third and last time, he met his guru Naropa. One morning, Naropa told him to get up, and as Marpa arose he saw the yidam Hevajra —a wrathful form of Avalokiteshvara and his own meditational deity—and his mandala appear vividly before him. As he stared in awe, Naropa asked whether he would prostrate before the yidam or before the lama. Marpa answered that he could meet his lama at any time, but that to have such a clear vision of his yidam and its mandala was very rare, and thus prostrated to the deity. Naropa snapped his fingers, saying, “But the deity is an emanation of the lama.” The deity, his celestial mansion, and the entire mandala dissolved into Naropa’s forehead.

Naropa then told Marpa that, because of this mistaken view, his religious lineage would remain long but his family lineage would not last. He also warned Marpa that he would not be able to attain full realization in that lifetime.

Therefore it is incorrect to hold the yidam as superior to the lama. It is essential to consider the lama and the yidam as of the same nature, inseparable from each other. When you practice tantra, you have to visualize the lama as one with Vajradhara, [the primordial Buddha]. If you practice on the basis that the lama and yidam are a single entity, there is hope for spiritual achievement.

There are four kinds of yidams belonging to the four classes of tantra: Action (Kriya), Performance (Charya), Yoga, and Highest Yoga (Anuttara Yoga) tantra.

The ability to practice a particular yidam comes from connections from past lives. Some may find it easier to achieve realization meditating on a heruka, others on Yamantaka, etc.

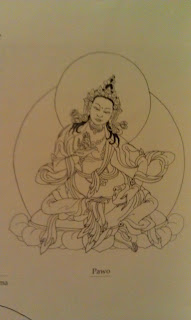

Yidams can have peaceful aspects, such as Tara, Avalokiteshvara (a.k.a. “Chenrezig” to Tibetans), or Mañjushrī; slightly [or semi-] wrathful aspects such as Vajrayogini or Guhyasamaja; or extremely wrathful aspects such as Yamantaka or Vajrakila(ya). It is said the yidams take on a fearful appearance in order to scare away the interfering forces who create obstacles for practitioners [and are thus motivated by compassion]. These obstructions can be internal, such as disturbing emotions, or external, and [are tamed via wrathful activity because they] cannot be tamed through peaceful means. The yidams themselves are not actually angry. Their apparent anger is motivated by love and compassion. They are aware that the beings afflicted by disturbing emotions or the obstructing spirits harming the practitioners are accumulating negative karma and will suffer greatly in the future, and thus the yidams take on those frightful aspects to actually lessen those beings’ suffering.

Wrathful deities can be compared to parents who have children with different dispositions. Although they love all their sons and daughters equally, the parents must treat their children differently for their own good. They reward those who have behaved well, but may need to punish or deal sternly with the unruly ones. They do not act out of anger, but rather out of concern.

All yidams assist the practitioner in overcoming the principal disturbing emotions: anger, desire, and ignorance. However, some have particular methods for taming particular disturbing emotions. By these means the practitioner can transform such emotions and take them on the path to enlightenment.

In the case of Yamantaka, for instance, anger is brought onto the path [and becomes a fuel for practice, rather than an obstacle to overcome]; the anger which arises in the practitioner’s mental continuum is used to eliminate anger. In the practice of Guhyasamaja, desire is generated which can eradicate desire. Like the termite born in the wood who eats the wood away, the anger or desire which are generated eat away the practitioner’s anger or desire.

Khandros and Pawos

The literal meaning of Khandro (mKha’ ‘gro) or Dakini is Sky-farer [or Sky-dancer]. There are several accounts of their origins. One holds that in the country of Uddiyana (“Orgyen” to the Tibetans) —said to be situated in the Swat valley of present day Pakistan—there lived harmful beings like ogres which were called Pawos (dpa’ bo) and ogresses which were called Khandros. As the tantric path developed and flourished in this area, these ogres and ogresses became Buddhist practitioners who attained high levels of realization [and thus proved once more the potential for Buddhahood in all beings]. Thus they became differentiated from the worldly demons who harm sentient beings. Khandros and Pawos—sky-farers and heroes—have attained at least the ‘path of seeing,’ at which stage they are free from rebirth in cyclic existence.

Another account has it that they were harmful beings appointed by Shiva and his consort Uma to guard the twenty four important sites. Because they brought harm to the beings there, they were eventually conquered by herukas and tamed. Reaching high levels of realization, they became beneficial guardians of these sites. The Pawos and Khandros represented in merit fields are of this latter type. They have attained liberation from Samsāra and are considered objects of refuge, members of the Sangha. Their main abode is Dagpa Khachö (bdag pa mkha’ spyod), the Sky-farers’ Pure Land and the buddhafield of Vajrayogini. These deities take various forms to help sentient beings, especially tantric practitioners, to progress upon the path.

Chökyang

When the Buddha was teaching, he instructed some of his disciples to remain as protectors (Dharmapāla, chos skyong), to ensure the long duration of the doctrine, to shield practitioners from harm, and to remove obstacles to their practices. Among them were the Kings of the Four Directions, who are represented guarding the doors of most Mahayāna Buddhist temples throughout Asia.

There are many types of protectors, such as those appropriate to the beings of the three motivations: lesser, middling, and great. Yama, the Lord of Death, is the guardian of beings of small capacity, whose chief motivation is to avoid the sufferings of the lower realms of animals, hungry ghosts, and the hells.

Yama distinguishes beings according to their accumulation of virtuous or unwholesome actions. In this way, he is the protector of virtuous beings, who are sent for rebirth in the higher realms.

Vaishrāvana is the protector of beings of middling capacity; those whose wish is to be freed from rebirth in cyclic existence and who adhere to ethics in the form of vows of individual liberation.

Vaishrāvana is the protector of beings of middling capacity; those whose wish is to be freed from rebirth in cyclic existence and who adhere to ethics in the form of vows of individual liberation.Mahakāla is an emanation of Avalokiteshvāra, an because he is the essence of compassion, he is the protector of the doctrine of the Great Vehicle [i.e. the Mahayāna].

Dharma Protectors listen to those who command them and hold them to their purpose. They help the holders of the doctrine: those who study it and those who practice it. Dharma protectors came into being at many different times: some were instigated by great Indian adepts (Mahasiddhas), and later, in Tibet, by Guru Padmasambhava.

There are two kinds of protectors: worldly and transcendental [i.e. unenlightened and enlightened]. Protectors such as Pälden Lhamo and Mahakāla are considered transcendental and thus have a place in the merit field; they belong to the Sangha and are objects of refuge. Some of those Dharmapālas introduced by Padmasambhava were considered worldly at the time, although they were virtuous beings who were totally committed to their pledges. Some say that, having continually practiced since the time of Guru Rinpoché, [these worldly protectors] have attained high levels of realization and are now beyond cyclic existence. In any case, because they were not [transcendent] when they were appointed, these protectors are not represented in the merit field.

It is considered wrong to view worldly protectors as objects of refuge. They are not to be prostrated to and must not be the main object of devotion. In Tibetan society, some protectors manifest themselves to humans through oracles. They have their mediums and are consulted about matters beyond human knowledge. People often pray to them for worldly purposes because they are more accessible than higher deities. However, they should only ever be considered to be helpers or friends. A true practitioner would only request their assistance for well-motivated purposes: something that will benefit others and be a source of accumulating merit. It is believed that, because of their pledges to help the doctrine, this is what pleases these protectors the most.

Yidams, Pawos, Khandros, and Dharma protectors are all aspects of the lama within the merit field. The lama correctly teaches the Buddhadharma to beings. The yidam is a form through which the Buddha tames beings and confers upon them the necessary initiations to practice tantra. Protectors are those who, instigated by the Buddha’s command, protect the doctrine and those beings who practice it correctly.

Any and all mistakes are my own. May the Great Black Eunuch Protector (Mahakāla, Gönpo Maning) and Grandmother Self-Arisen Tāra (Achi Chökyi Drölma) protect beings from misconceptions, misunderstanding, ignorance, and all other obstacles! May all beings benefit!

CHOGTRUL TENGA RINPOCHE

THUG GONG CHÖYING CHIGSE KYANG

LARYANG TENDRO CHICHE LE

TRULPE DASHAL NYUR CHAR SOL

LARYANG TENDRO CHICHE LE

TRULPE DASHAL NYUR CHAR SOL

Surpreme emanation, Kyabje Tenga Rinpoché, Although you have merged your intention into one with Dharmadathu, For the sake of the Doctrine and beings, in general and in particular, May the moon-like face of your emanation rise again soon!

Composed by Sangyé Nyenpa

This supplication was composed by H.E. Sangye Nyenpa Rinpoche in the early hours of 30th March 2012, in the presence of the precious remains of Kyabje Tenga Rinpoche. Immediatedly translated by Sherab Drimé (Thomas Roth).

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1) According to Gapé Lama Thubten Nyima, if the practitioner meditates on the seed-syllable associated with the yidam and visualizes it residing at one's heart center, being three dimensional, and emanating light to benefit sentient beings, this is a sufficient visualization which invokes the blessings of the deity. The external yidam which typically is invited to reside in front of the practitioner---the wisdom being or jñanasattva---arises from the seed-syllable upon a lotus and either sun or moon disc, and the self-generated deity---the samayasattva---likewise arises from and dissolves into the seed-syllable at one's heart center. The seed-syllable is thus called the meditation being or samadhisattva, as relying on simply the seed-syllable and confidence that both the yidam is present before you and your buddha-nature is manifesting as the deity is sufficient for productive meditation.